From Sicily to Little Italy

Plates piled high with spaghetti and meatballs, veal Parmesan buried under a blanket of cheese, long-simmered tomato sauces—these classic Italian-American dishes are Sicilian innovations, even though few Sicilians ever ate them before coming to the U.S. Between 1876 and 1924, almost one-third of Italy’s population immigrated to America. Most came from poverty-stricken regions of the rural south and Sicily. As Nancy Verde Barr describes in her fascinating cookbook We Called it Macaroni, theirs was a classic cucina povera, peasant food that made a bounty out of humble ingredients. When they came to the U.S., however, that began to change.

At home in Italy, Sicilians coated eggplant or zucchini with stale breadcrumbs to make vegetarian Parmesan. Chicken and veal we’re luxury ingredients. Thanks to the island’s mild climate and rich volcanic soil, tomatoes grew year round and the sauces made with them were fresh and quickly cooked. Pasta was served in small portions before the main course, lightly dressed with simple ingredients like raisins, fennel, and fresh sardines. Fish and eggs were the featured proteins, meat reserved for celebrations. But as they acclimated to life in a new country, Sicilians changed not only what they ate, but how the world thought about Italian food.

Most of these immigrants settled in cities like New York, Boston, and Providence, Rhode Island (places, not incidentally, near the coasts, where they could still fish). Though they left behind an agrarian life, they continued to grow vegetables wherever they could—in backyards, on rooftops, and windowsills. They opened food markets that catered to other Sicilians, from traditional bakeries to fish carts. For a while, at least, they continued to eat as they always had.

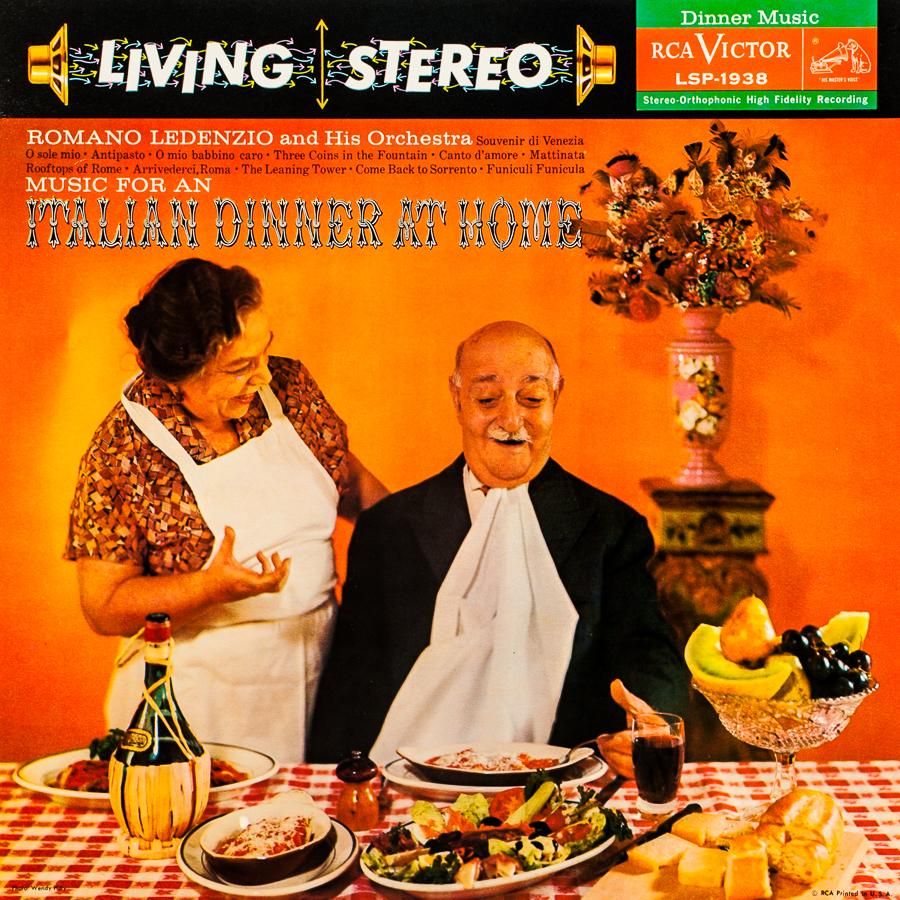

As they became more affluent, Sicilians started eating more meat and upping the portion of cheese in their macaroni. Their new neighbors, not all of them Italian, didn’t always appreciate the pungent flavors of prized ingredients like wild mint, peperoncino, and salt cod. Sicilian cooks learned to tame their tastes and their food became richer, the portions bigger, and the flavors less bold. Eventually, these immigrants gave birth to a new cuisine, an Italian-American hybrid celebrated in red-tablecloth restaurants where candles stuffed into chianti bottles illuminate meals that would be unrecognizable in their native Sicily.