Persia: The Gourmet Ghetto of the Ancient World

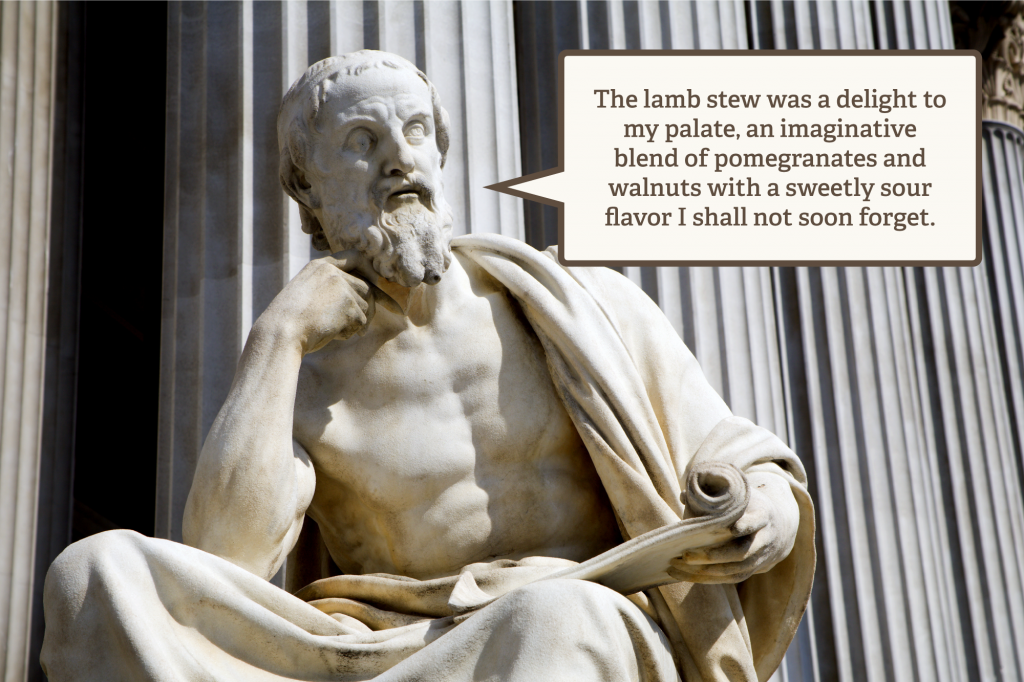

Long before places like Berkeley, New York, and Copenhagen became famous for their celebrity chefs and farm-to-table menus, Persia had a cutting-edge food scene with quite the following. Fanboys like the Greek historian Herodotus heaped praise on the local cuisine as far back as the 5th century BCE. Persian line cooks from the 8th to the 13th centuries were the first choice of the Arab-Muslim dynasty when they needed to impress heads of state with a fancy meal. Even Alexander the Great, who took down the Persian Empire and turned up his nose at the food (he thought it was overly extravagant), raided the larder and rode out of town with his bags packed full of the country’s finest ingredients.

It wasn’t just the cooks who helped make Persia a destination for the food obsessed. Ancient engineers established a sophisticated road system, which allowed ingredients to be transported across the empire. Long before Airbnb rolled into Tehran, hoteliers there opened caravansaries—inns that offered travelers on the Silk Route a chance to sample the local fare. And then there were the tech geeks who designed qanats, pioneering underground aquifers that brought water from the perpetually snow-packed Alborz Mountains to the desert plains. Their innovation turned the arid parts of the country into a magnificent—if artificially fertile—region unlike any other in the Middle East. Thirsty crops like almonds, cherries, pistachios, and cucumbers, which are impossible to grow in most bordering countries, thrive in the Iranian desert. (Modern engineers might want to rethink that design as Iran’s once-lush farmlands are sinking and the soil beginning to crack due to dwindling water supplies.)

The country’s dizzying history of political upheaval has presented its share of problems, but turmoil has in many ways served the country’s kitchens very well. Over centuries, Iran has expanded and contracted its periphery many times, and with each redrawing of the border, its pantry has grown. (Hello, turmeric, rice, and tomatoes.) Persia has had its share of well-received exports as well, including ice cream, apricots, and kebabs.

Despite the changes, the food has in many ways remained the same for centuries. It’s very likely that the dishes that caught Herodotus’ attention are still prepared in Iranian kitchens today. Stone tablets dating to 515 BCE unearthed at the temple of Persepolis were etched with lists that included lamb, walnuts, and pomegranates, ingredients for fesenjan, a classic stew that’s still served at weddings and other special occasions.