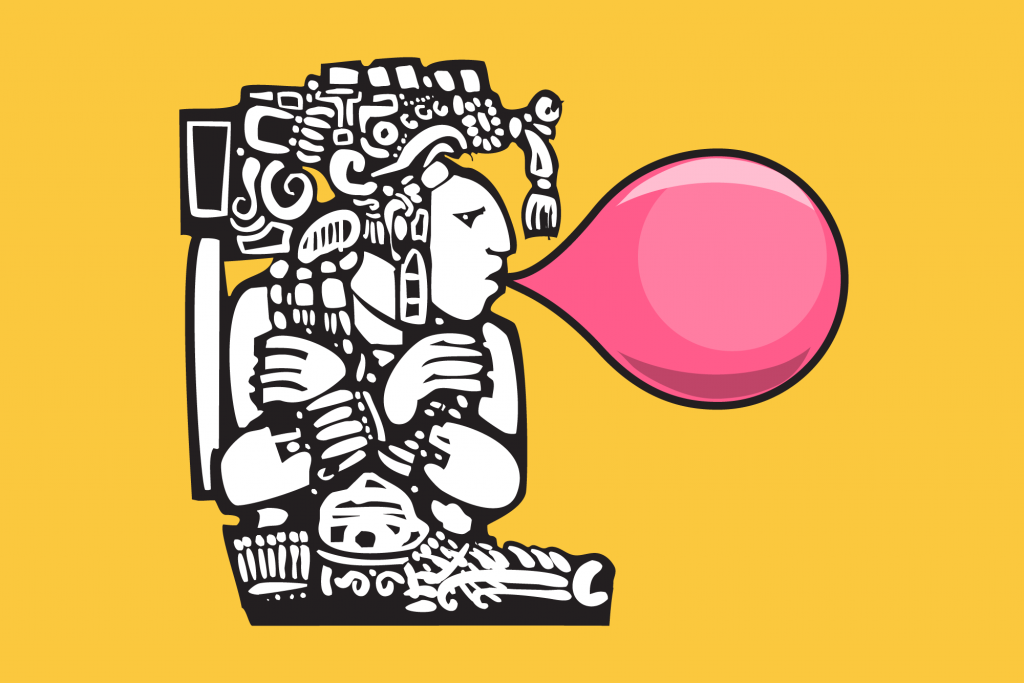

The Great Maya Chewing Gum Bubble

The early Maya chewed chicle (pronounced cheek-lay), a latex extract from the sapodilla tree, to care for their teeth and ward off hunger, helpful while building massive stone monuments. Chicle was also used as a craft glue and building material (but that’s another story). Though the ancient Maya mysteriously disappeared from their cities around 880 CE, chicle lives on, sparking a 20th-century chewing gum empire and the 21st-century resurgence of organic craft chewing gum.

At the end of the 19th century, William Wrigley Jr. helped Americans develop a taste for chicle with his famous brand. The Chicago businessman began an aggressive marketing campaign, which included sending his gum to all the addresses listed in the phone books for every state. The success of that effort created a bull market for the Yucatecan chicle trade. The Maya people used the profits from the sale of chicle to fund their revolution against the Mexican government. The chicleros, who harvested the resin, enjoyed a boost to their fortunes brought on by this golden age of chewing gum.

The tale took a familiar turn when demand outstripped the chicle supply. Though it’s recommended that the trees rest for five to eight years between harvests, in order to satisfy the booming gum market, extractors overtapped the forests. By 1930, at least a quarter of Mexico’s sapodilla trees were gone. Chewing gum manufacturers turned to synthetic bases, and the chicle bubble burst.

Fast-forward to the modern day, when demand for artisan products extends even to candy. A handful of producers, including Glee Gum and Chicza, are buying chicle from the Yucatan, working with native communities to sustainably harvest the trees, and making certain that the Maya’s sweetest contribution sticks around for a long time to come.